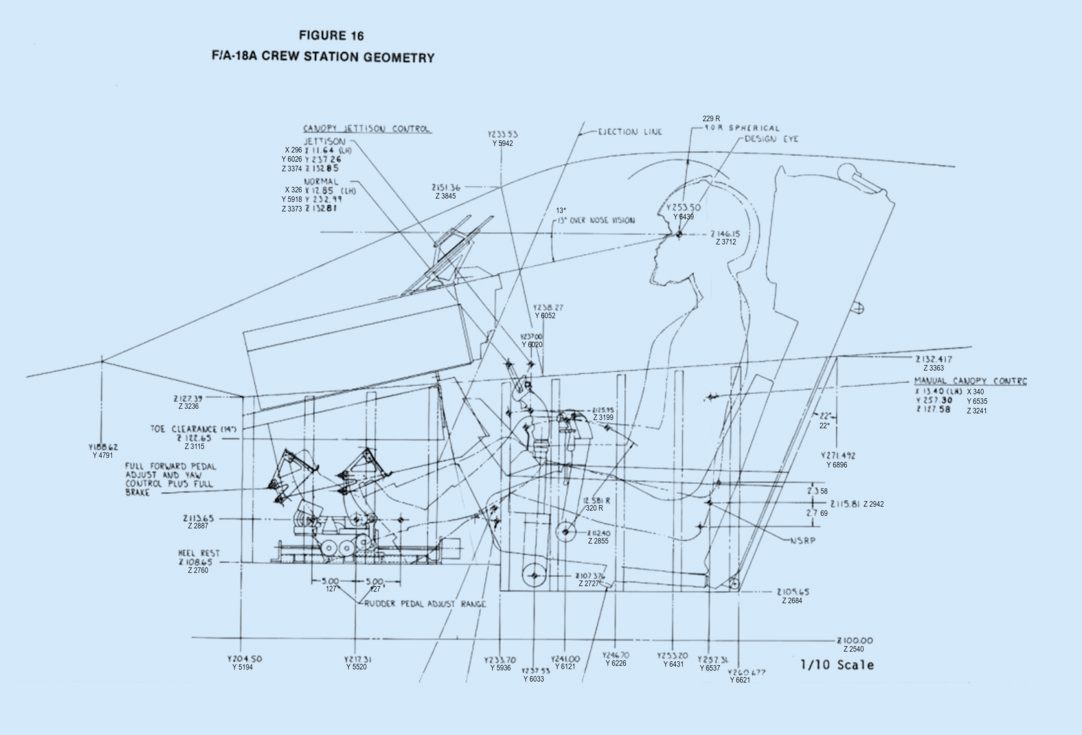

The prototype cockpit was designed based on some very old measurements taken from pilots in the 1920s. The size and shape of the seat, the distance to the pedals and stick, the height of the windshield, were all built to conform to the average dimensions of a 1926 pilot. So in 1950, they asked researchers to calculate the new average.

So this led to quite an intensive user research investigation and the largest study of pilots that had ever been undertaken. More than 4,000 pilots were measured - 140 dimensions of size, including thumb length, inseam height, and the distance from a pilot’s eye to his ear, were measured and then the average for each of these dimensions was calculated. But one of the researchers, Gilbert S Daniels, would later become famous for daring to ask the question: How many pilots really were average?

Applying just ten of the size dimensions, Daniels found that none of the over 4000 pilots measured was average on all ten dimensions. When looking at just three dimensions, still less than five percent were average.

.png)

So instead of making a cockpit of mediocrity for everyone, the team embraced designing for customizability. This had led to a lot of features that you now experience when getting into a car such as reclining your seat 5 different dimensions or adjusting your side mirrors...